This book provides you with a number of new mental models in which to view the contemporary world.

Touching on areas of history, science and developmental economics this book acts as a big update of some topics you may not have revisited since secondary school.

Perhaps a weakness of the book is the fleeting explanations of why we have formed these instincts. For example, in the first chapter on The Gap Instinct, there is a vague discussion of ‘us versus them’ and a link towards how this served us as hunter-gatherers, but it doesn’t go into much depth. Given that these instincts form the foundation of the book, I would have liked a little more detail on how exactly they came to be.

A strength of the book is certainly its structure. They do a good job of organising the data, arguments and anecdotes (which is what fills the pages) in a way that leaves you with 10 clear actionable points for your day to day life moving forward.

Rating - 8/10.

View on Amazon here: Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About The World - And Why Things Are Better Than You Think.

You can view my other book notes, ratings and recommendations on my books page.

Summary

In general, smart and educated people massively underperform in a fact-based quiz of the world. (Worse than random). An accurate fact-based view of the world is that the world is generally getting better, year on year, in almost every way. Although the dramatic world-view says its getting worse. Why? Years of evolution. Our monkey brain jumps to conclusions and fills in gaps (often incorrectly). It takes effort to see the fact-based truth. In this book, the emphasis is on critical thought to replace assumptions and immediate reactions…

The Gap Instinct

Occurs when we think of two distinct groups with a huge gap in between. For example, we dod this with the developed vs developing world. But, let’s take child mortality. Decreased in every country over last 50 years. There is no longer a divide as there was in the 60s, but rather all trending positively with the large majority in the middle. i.e. there is no gap at all between many nations. The new normal is a large middle.

So we should replace our old dichotomy with an updated view of income groups.

- Level 1: < $2 = 1bn people.

- Level 2: $2 - $8 = 3bn people.

- Level 3: $8 - $32 = 2bn people.

- Level 4: > $32 = 1bn people.

So 5/7 of people are actually in the middle. WEF adopted these income brackets yet most of the world still think in the old paradigm.

Why do we think this way? It seems to be a natural urge for humans to think in dichotomies. But it also makes for better stories (in media, news, films, etc).

Fight the instinct

- Beware averages - Averages can be very deceiving. Take math averages between girls and boys. If you change to a spread on given year, there is actually a 95% overlap = no gap at all. So have to remember to drill down as well.

- Beware extremes cases - They can misinform the general trend. E.g. Brazil income spread is one of the largest in the world. But its also at an all-time low. And if you use the above 4 groups, still the majority are in the middle.

- View from the top - On L4 we only see L1/L2 through the media. And the media is almost never representative. They dramatise.

So beware of our sources and their biases. Remember, when a story paints a picture of a gap - Look for the majority. Are they in the middle?

The Negativity Instinct

Is when we more readily recognise the bad than the good.

This isn’t saying some things haven’t got worse (e.g. sea levels, terrorism, endangered animals). But we recognise these things more than the things getting better - the slow burn of human progress (small, daily, incremental positive changes).

Examples

- Extreme poverty at lowest - halves in last 20 years.

- Life expectancy at highest, 72 worldwide.

Features of negativity instinct

- Things were worse than we remember - We forget how bad things were. E.g. Children find child bones all the time, but we forget how high child deaths were. Personal experience in Cambodia. The deaths of children so recent!

- Selective reporting - Reporters and lobbyists spin things to exaggerate for their cause (knowing that doing so can in the short term make them more effective)

- Feeling rather than thinking - We feel problems strongly even though intellectually we know stuff is getting better (but child deaths still hurt a lot). This is human irrationality.

Fight the instinct

- Bad and better - A mindset that appreciates things can be bad, but still getting better.

- Expect bad news, and ask for positive - Bad news will be delivered, but good news you have to look for1. Ask yourself - what is the good news?

- Don’t censor the past - View it with correctness.

So we are more likely to hear about bad news than good news. We should, therefore, compensate for this in our mind. This is a bias we should correct for.

Straight Line Instinct

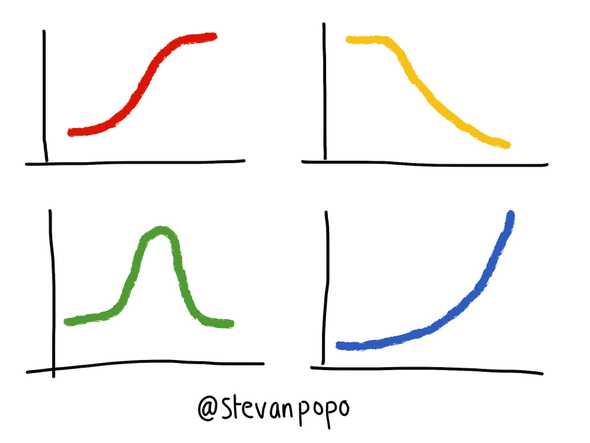

When we see some data and assume it will continue as a straight line, with the same velocity. This is incorrect, as often it can change in many ways.

Examples

- Population, people see population and assume it’s going to keep growing. In fact, its expected/predicted to stop and maintain a new steady state (this is because of natural process of increased education and contraceptives).

- Children’s height - We know at some point it tails off.

The biggest connector between the number of children per mother is wealth. Poor have more. Rich have less.

Fight the instinct

Remember not all lines are straight2, so check your assumptions:

- Straight - income against health, marriage age, wealth spent on culture, years in school.

- S-bends - Flat in L1, then rise through 2-3 then flatten again in 4. e.g. vaccinations, primary education, fridges in household

- Slides - start high in L1, then lower into L2 and L3, flat in L4. Children per mother.

- Hump - Hump in middle, where at each end they are low (but mean different things). e.g. cavities and motor deaths (How can you have motor deaths with now motors? Cavities with no teeth?).

- Doubling lines/exponentials - Often things related to money, as money behaves in this way. Also: emissions, distance travelled, dollar spent on cars.

The Fear Instinct

Fear is an evolutionary tool to keep us alive. But when we are scared, we make terrible decisions/judgements.

The Attention filter

We receive so much info, we filter it. One thing that gets through filter, is fear or dangerous things. So media play up to it3. Three main fears: physical harm, captivation, or poison (used to be helpful but not so much anymore unless you’re on L1 e.g. snakes).

In the news, terror and hostage cases are particularly powerful. Yet paradox - it’s also the safest time the world ever been. It’s not the media’s fault. They just serve what gets through our filter (so its how we consume media that is problematic).

- Natural disasters - Still happen, but we better protected against them as less of us on L1. Infrastructure to help and relief aid.

- Aviation - Through global cooperation, we’ve vastly improved safety.

- War & Conflict - (Bad but better), death from wars far less globally. Bigger multiplier than ever as war ruins trade, economic growth, etc.

- Contamination - Fear of nuclear war is possible, but often the fear is worse than the actuality.

- Terrorism - Gone up. But reduced on L4. Largely in 5 countries. But also tiny compared to say car deaths. So what should we really fear?

So we need to manage our fear and look at the data. What should we actually be scared of? The perceived fear of terrorism is far greater than the actual threat. Whereas deaths from obesity or alcohol-related are much larger.

Fight the instinct

- Remember that when we hear something scary, often its selected for exactly that reason (not because it’s probable). So calculate: risk = danger x potential exposure. Is it really a threat to you?

- Don’t make decisions under fear.

Use data to understand what really is scary, and realign on that.

The Size Instinct

Is when we give too much creed to one lonely number or one particular victim. Coupled with the negativity instinct, it is why we often get things systematically wrong. E.g. spending healthcare budget on someone right in front of us who is almost certainly dead vs preventable diseases outside the hospital.

Fight the instinct

- Compare numbers - Never leave a number alone. Numbers always look big in isolation. Find a number to compare it to. E.g. actual baby deaths seem high, but low if compared to the previous year.

- 80/20 rule - Focus on the 80 and drill down. E.g. population is spread 1-1-1-4. And estimated 1-1-4-5 by 2040. So to solve climate change, focus on Asia/Africa makes a lot of sense.

- Divide - Some numbers make more sense in relation to another number. Example, GDP or emissions (per person). Look for the rate.

Always remember these ways of giving a number context.

The Generalisation Instinct

Categories are a useful tool we use to frame our thoughts. They allow us to quickly identify a group of people and generalise. But incorrect categories give us a misinformed view of the world. For example, by wrongly identifying the world as only developed vs developing world FMCG brands are missing out on potential customers in L2 and L3 countries. Or by wrongly identifying all youths in the street as criminals, parents are worrying too much about street crime.

The reality is that many of us hold incorrect categories (generalisations/stereotypes) in our heads. We would have a more fact-based worldview if we updated these with better, more accurate or more specific stereotypes. A good way to do this is by travel as you get to see places first hand.

Fight the instinct

- Look for differences between groups & similarities across groups - For example, when we look at the ways different countries prepare food, we see that China and Nigeria use similar tools and means. This isn’t to do with culture (which would be a false categorisation) but rather income group (which would be more accurate).

- Beware majorities - A majority can be anything over 50%. But there can be large differences in meaning between 51% and 99%, so stating simply ‘a majority’ can be a false classification.

- Beware exceptional examples - Making generalisation from exceptional examples is also a bad idea. For example, does one dangerous chemical make all chemicals bad? Does one good chemical make them all good?

- Assume you are not normal and people are not stupid - As someone on an L4 income, when you see something that may seem stupid, ask yourself in what ways is it actually smart? For example, Tunisian’s build there houses brick by brick so that they don’t have to store the bricks where they become at risk of theft.

- Don’t make generalisations across incomparable groups.

The Destiny Instinct

The destiny instinct is when we believe that the characteristics of a culture, society or religion are unchangeable. For example, the notion that Africa will not become a modern society, it’s not in their culture. This is of course false. We mistake slow change for no change at all. Slow change is less newsworthy, so fewer people are aware of it.

This instinct may have served an evolutionary past. Hunter-gatherers surroundings rarely changed, so they were safe to assume things stayed the same.

Examples

- Africa can’t catch up - False. Some of the countries are already performing very well (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya). Even if you take out North African leaders, there has been progress in education and child mortality. African countries look much like South Asian countries before their economic boom - so why can’t they progress? In fact, it would be an anomaly if they didn’t catch up.

- Babies and religion - There is a notion that people of particular religious beliefs have more babies. False. For example, Iran had the fastest drop in children per woman from 1990. Now women in Iran have fewer babies than those in the US. The link between the number of children and religion is far less clear that children and income. It is clear that families on L1 income (poor) have most babies and those on higher income levels, have less.

- Patriarchal culture change - There is a notion that certain cultures have more patriarchal views. False. Sweden, which is now very forward-thinking in terms of women’s rights was once a patriarchy with stay-at-home mums (as in say, Asia now). But once women had equal education and started earning higher incomes, the culture changed with it. What is to say the same thing won’t happen in Asia?

Fight the instinct

- Slow change is not no change - Very small percentage changes on a yearly basis accrue to large changes over time. For example, the first piece of protected land in 3rd Century was insignificant. Then 2,000 years later the first Western country protected land. Slowly, more countries did. Now 15% of the earth’s land is protected.

- Update your knowledge - Math and science rarely change. But social sciences need updating regularly.

- Talk to grandpa - See what older generations thought vs what they think now. Understand that things change over time.

- Collect counterexamples - Whenever you see a fixed judgement made on a country, think of another country that did the oposite.

So remember, very few things are constant or unchanging. Over time, small changes, year on year can total up to a big difference, whether that is in culture, religion or economy.

The Single Perspective Instinct

This instinct is the idea that we favour simple problems with simple solutions. For examples, free markets are always best for society and regulation should always be removed. It’s easier to hold this view than to hold a more nuanced view that considers different groups, complexities and edge-cases.

Two views of the world

Experts - Have a useful view of the world. They do important research and gather data. If all experts in a field agree, it is probably telling. Similarly, if none of them agree, it shows the field is complex or perhaps doesn’t have enough data yet. But there are downsides to expert knowledge:

- Outside their domain - Experts are not experts in everything.

- Sometimes experts aren’t experts in their own domain - For example, activists who claim to be experts can have skewed and extreme views on a subject.

- Give someone a hammer and everything is a nail - If experts overapply their knowledge, it is no longer useful.

- Avoid armchair experts - Looking at data is only part of gathering facts. You also need to look at people and see if the numbers match up with what you see in the real world.

Ideologues - Are another example of where we can hold onto a single view too strongly. For example, take Cuba and USA as two examples. Cuba, a communist state, achieved the same level of health care for their population as the USA, in spite of being a far worse performing economy. The USA, a free market nation, has relatively poor performing health measures, despite outperforming all other economic measures. In both these cases, could each country benefit by holding on less tightly to their political ideologue? Most probably.

No idea is free from being scrutinized. Take democracy, which most people would see as the top of a political hierarchy. Yet many countries have achieved fantastic economic results without democracy. So democracy isn’t the only way to do things. In fact, its more of a goal itself.

Fight the instinct

The best way to fight the single perspective is to have a toolbox4 that allows you to:

- Test ideas - With opposing views. How do they hold up?

- Limit expertise - Only to your field or the field they are applicable.

- Don’t use your knowledge as a hammer - No one tool is good for all problems.

- Look beyond numbers.

- Beware simple problems with simple solutions - Often things are more complex. So analyze each issue on a case by case basis and view its merits5.

The Blame Instinct

Is when we seek one simple reason (or person) for a bad outcome. This instinct causes us to oversimplify problems and blinds us from learning the true (usually multiple) causes. It also causes us to give too much agency to individuals.

Example

- Why are children becoming more violent? Violent video games! Really? Perhaps that is one factor. But what about violent films? Or increased marginalisation? Or more easily available weapons? etc. It’s rarely one simple answer.

Note - We can also use the blame instinct for positive outcomes. Where we prescribe too much praise on an individual. Blame and claim are interchangeable.

Who we blame

- Big bad corporations - For ripping us off, for false advertising to us, etc.

- Journalists/Media - Are as wrong as the rest of us. But we rarely ask why so? Often its because they are misrepresented or misinformed themselves.

- Refugees - Children drowned at sea when smugglers boats capsized. We blamed them. Yet nations signed up to the Geneva convention but then didn’t provide the infrastructure support to allow safe passage for those claiming asylum. Airports turned them away and proper boats were limited. Who was really to blame?

- Foreigners - There is a tendency to blame ‘them’. Syphilis in Russia was known as the Polish disease. In Poland, it was known as the German disease.

Blame & Claim

This instinct to blame means we often give too much credit to powerful individuals.

- Political Leaders - People credit the reduction in children per mother to Mao’s one-child policy. But in the 10 years before the policy children dropped from 6 to 3. And during the policy, it never actually went lower than 1.5. Similarly, the Pope is heald as a strong leader who condemns the use of contraception. Yet the use of contraception around the world is about 60% and is very similar in both Catholic and non-Catholic countries.

So it’s less to do with political leaders and more to do with:

- Institutions - All the smaller pieces and people that makeup society as a whole. Each contributes to progress more than any one individual.

- Technology - Tech allows us to get more efficient. It pushes the frontier forward for all of society.

These two forces should get more credit when things go well.

Fight the instinct

- Look for causes, not villains - Accept that bad things can happen without anyone intending for them too. Spend your time understanding the multiple interacting causes, or the system, that created the situation.

- Look for systems, not heroes - When someone claims to have caused something good, ask yourself if it might have happened anyway, regardless of the individual.

The Urgency Instinct

Is triggered when people rush us into a decision. Under urgency, we are less analytical and less rational. We make poorer decisions under time pressure6. For example, activists may make knife crime seem like an urgent and critical matter in order to galvanize resources.

This instinct may have served us in the past7. Hunter-gatherers in the wilderness were more likely to survive say a lion attack if they could react quickly with little information. But now that these primary risks are eliminated we need more analytical, thoughtful thinking.

Fight the instinct

- Focus on data - All problems should start with a good data set that we can track over time.

- Don’t overstate issues - For example, some activists will overstate certain issues as a means to persuade and incite action. But over time this can damage the credibility of the movement.

Five real fears

Here are some examples of issues we should fear moving forward. 3 have happened before, 2 are happening now.

- Global pandemic - e.g. Spanish flu of the past.

- Financial collapse - Has happened on many previous occasions. And now economies are so linked that it would have even larger effects.

- WW3 - Many countries with huge military force and history of violence.

- Climate change - It is certainly happening and would require huge collective worldwide effort to change behaviours, starting with L4 economies.

- Extreme poverty - Is already a reality for many countries. It causes many of the other issues people face. We already know the solutions but just need to keep executing.

In short, be aware when someone is trying to trigger your urgency instinct. Instead, take a step back and consider the big picture. Make sure you have all the data you need. Focus on the real issues and make an informed, thoughtful choice8.

Factfulness In Practice

Factfulness is important across society to ensure we have an accurate worldview in which to make decisions.

Education

- Teach humility - Teach children that our instincts make us vulnerable to mistakes and that we should be willing to change our mind in light of new data or research.

- Encourage curiosity - Actively seek new information and learn points of view that are opposed to our worldview.

Ideally, we would have a mechanism whereby we can refresh the information everyone was taught at school when it no longer becomes valid.

Business

- Sales & Marketing - A better understanding of current economies and future markets e.g. Asia and Africa.

- Recruitment - Companies are global and talented individuals are everywhere.

- Investing - Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya are massive opportunities.

- Production - Globalisation continues and manufacturing will likely shift to Africa as South Asian countries diversify into service-based economies.

Journalists, Activist & Media

It’s hard to see a scenario where they will be factful, so its important that we can acknowledge their limitations and react accordingly.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, it is to our benefit to have a factful worldview. Like navigating with a GPS, it is easier to know what decisions to make in the world if our worldview is accurate. It can also be happier and more stress-free, as we deal with issues in their correct context.

-

An odd connection, but the chapter on the Negativity Instinct made me think of The Dalai Lama's Art of Happiness. He also talks about seeking out good news, in order to more readily balance the bad news which is abundant to us.

↩ -

This is a good example of why Charlie Munger calls for the use of many mental models. If you only have one mental model, in this case straight lines, you are bound to see many data points in an incorrect way. If however, you expand your mental models to include all the possibilities, you can choose the correct mental model for the correct scenarios, increasing your chances of a Factful worldview.

↩ -

Part of what sets humans apart from other species is our ability to create stories (see Sapiens). This is true for the media, who are professionals in telling stories that are captivating and emotional.

↩ -

The notion of a toolbox made me think of How To Read by Mortimer Adler. The book discusses techniques to read properly, where the end goal is for understanding and correctness. Similarly here, the toolbox is to encourage almost a discussion in your own mind where the end product is correctness (a factful worldview).

↩ -

Again, mental models. Complex issues require analysis from different lenses.

↩ -

Thinking Fast And Slow - A great book by Daniel Kahneman. What Daniel calls system 2 thinking, slow, effortful, thoughtful, decisions are exactly what is bypasses when our urgency instinct is triggered.

↩ -

I've often heard this referred to as 'the monkey brain'. The monkey brain served us well in earlier times but can often trip us up in the contemporary surroundings.

↩ -

This reminds me to focus on second-order thinking. i.e. thinking through an action, but also the knock-on effects from that action. The urgency instinct deprives us of the time to carry out this second-order thinking.

↩

You can view my other book notes, ratings and recommendations on my books page.